WILLIAM CORWIN:

Lethe-wards at Geary Contemporary

2022

In the window of Geary Contemporary, an intimate gallery in the middle of a charming upstate New York village, sits an incongruous tableau—a roughly-made iron boat impaled on a ladder. The object’s pathos and obvious mass emit enough gravity to draw the viewer closer. Peering through the glass, one can see more boats strewn inside. Their configuration resembles the remains of an ancient nautical funerary procession, empty of mourners, set adrift on a placid sea of thick maple plywood, ringed by smaller satellites and flanked by two bulbous sentries perched on wall-mounted sills.

“Lethe-wards,” William Corwin’s solo exhibition (on view through December 18, 2022), reads at first like a grim ode to humanity’s earliest means of conveyance. Boats are a staple of legend, both the tether binding us to a primordial aquatic ancestry and the ultimate peripatetic instrument. For more than 8,000 years, they have constituted a near-universal totem of human traversal, forms embodying escape and eschaton, implements of adventure, as well as adventure’s end.

But there’s more going on here. Once inside the gallery, the initial solemnity is undercut by the wry typographical jab of Lethe-wards Had Sunk. The sculpture’s title is spelled out in bas-relief inside its blackened iron bulk, stencil-formed sans-serif capitals speaking the visual language of military provisions. The Lethe, one of the five rivers in the underworld of Hades, was a mythical channel to forgetfulness. In ancient Greek, the word “lethe” means oblivion—an oft-pursued state, elusive and addictive. This boat didn’t survive the trip, and its absent captain is doomed to an eternal remembrance, denied the freedom of forgetting.

Suddenly, we realize that we are mired in a Devil’s Rectangle of failed vessels and are moved by an irrepressible compulsion to verify just how heavy these eight “boats” are. Closer inspection of Long Boat, One Passenger and Little Curragh provides evidence of Corwin’s quixotic decisions and reveals the peculiar details of his material dissonance. The coarse-woven jute texture of the heavy metal shells evokes the warp and weft of ancient maritime hymns; the roughly severed bowsprits, glinting umbilical remnants of the molding process polished by the abrupt bite of the cut-off wheel, draw attention to the crucible of their scorched birth; and finally, there are the ladders, which languish in every boat but one.

That first sculpture in the window, The People All Said Sit Down, Sit Down You’re Rockin’ the Boat, suggests a strange violence. Here, the ladder does not emerge from the boat, but pierces it, as if Charon’s ferry had the misfortune of dropping from its mythical travails straight onto the honed blade of human ascendency. This ladder is upright, robust, priapic—strong enough to sink a ship. All the other ladders look beat up, defeated, slumped like refugees in useless life rafts, exhausted from their unrecognized toil under the legions who have climbed them, grizzled veterans rescued from the trenches of relentless ambition.

Attention finally turns to the two inchoate figures first mistaken for sentries. Their inscribed names—Artemis and Artemis Ephesia—are puzzling. It takes a while for their relevance to crystallize. The Huntress and The Mother. Ladders and Vessels. Ambition and Nurturing? Wait. These boats cannot float. Artemis, the virgin goddess of the hunt and fertility, was sworn never to marry, never to bear children: a mother, denied. Oh. Corwin’s deliberate and masterful material catachresis reveals itself as a compelling paean to frustration and futility. The very emblems of buoyancy, cast in iron, become the stuff of shackles.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

MATT KENYON & JASON J. FERGUSON:

Homing at Buffalo Arts Studio

2022

Framed by a spotlight, a towering pyramid of overly full champagne glasses tempts the fates. Were this a wedding reception and not a gallery, one could easily picture a small excited ring-bearer drunk on attention and non-alcoholic punch bringing it down in a cataclysm of booze-drenched shards. Looking carefully, the imagined cries and tinkling glass fade away, and we realize there is indeed cataclysm. But it is slow, quiet, and inexorable. At the bottom of every glass in Matt Kenyon’s elegant and brutal Kicking the Ladder lies a drowned American Dream—a tiny transparent effigy of a house, immersed in water, nearly invisible but for its refracted outline, plopped into a cruel celebratory landscape. A ghostly flyer lies at our feet, sneering with opportunistic intent: “We Buy Houses.”

Jason J Ferguson’s startling Receptacle sits nearby, a white-washed 55-gallon Rubbermaid BRUTE trashcan, encrusted with 10th-century Italian ornament. A jarring juxtaposition of refuse and reliquary, it is also a wry commentary on the relentless American obsession with material culture that brings to mind a snippet from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Ode: “Things are in the saddle, and ride mankind.” Ferguson’s pointed admonition seems to rattle the tightly shut lid: we enshrine what should have been discarded long ago.

These two works at the heart of “Homing” (on view through November 4, 2022) complement each other well. The fragile domesticity to which they allude coalesces fully from a distance, when we realize that there is another champagne glass pyramid hanging inverted over the first, its cast shadow balancing precariously on top, a mortgaged-to-the-hilt Sword of Damocles. Comprehension dawns: everything we love is at imminent risk, and we are ourselves to blame.

With that, the significance of the surrounding smaller works snaps into focus. Each one offers a meditation on the futile urge to commemorate through technology. Kenyon’s Notepad, Alternative Rule, and Log Rule, three thick reams of paper bearing only the pale blue and red markings that suggest their uses, appear blank, but are, in fact, already full. Under a viewer-operated endoscopic device, the ruled lines reveal their secrets on a wall-mounted video monitor—an exhaustive accounting of the damage wrought by guns, war, and cruelty; thousands upon thousands of names memorialized in threads of tightly packed microscopic text, never to be uttered again with anything but sorrow. Visitors are invited to write letters of protest to elected officials on these hallowed pages, contributing their missives to a clandestine memorial, archived by the Library of Congress.

By now, the viewer has been reduced to a tearful pinball, bouncing from one heartbreaking specter to the next. Ferguson’s small Home vignettes are fragments of 3D scans of an aging house, all 3D-printed in a cold ultramarine blue resin and confined to acrylic vitrines. In HOME-21-LAT42-LONG-84-002, an empty sagging living room chair strewn with a haphazardly flung blanket makes for a particularly mournful ode to absence, its once-cozy invitation relegated to unyielding plastic. All of these encapsulated intimacies, as well as HOME-21-LAT42-LONG-84-010 (the life-size replica dominating the adjacent wall), exude the detachment of alien scientific curiosities, specimens taken note of, examined closely, then filed away.

Indeed, the warmth has been leeched from every surface in “Homing,” not because the artists lack humanity, but because of all the damning evidence they have accrued while desperately mining the souls of our technologies and illuminating their injustices. In their tandem indictment, Kenyon and Ferguson have declared that the true tragedy may be all the faith we have placed in human ingenuity, believing it to be a bulwark against our ever-increasing self-inflicted entropy.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

MATT KENYON:

The Wolf at the Door

2021

Matt Kenyon’s Empathy Machines

(from CORNELIA, Issue 5.1)

The Wolf at the Door, artist and University at Buffalo professor Matt Kenyon’s extraordinary requiem for humanity, conscripts us the moment we walk into Buffalo’s storied Big Orbit Gallery. Masked due to COVID-19, our identities effectively obscured, we ourselves become unwitting objects in Kenyon’s indictment of hegemony. The trappings of social distancing amplify every work in the exhibition, driving home its poignant central theme: our most vulnerable have been consigned to the periphery, and those of us with the privilege to be visiting an art gallery during a pandemic are implicated.

Sheep do this. In herds, the strongest burrow into the centers of the tight clumps of wool and flesh that quickly form in reaction to external threats, relegating their weaker members to the edges to appease the circling wolves. It’s a simple survival instinct, untainted by retrospective guilt. But when it comes to humans, the specter of complicity is harder to evade, and the external threat is almost always a wolf of our own devising. In making this point, Kenyon’s kinetic and mechanistic works display a profound sense of affinity with their audience — and what a rarity it is to find humor (albeit dark), sincerity, and empathy embodied by metal, plastic, glass, and wiring.

Artists have engaged in innovative mechanical investigations since well before the time of Leonardo da Vinci, the most familiar example of the polymath archetype. In Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, the geographer Jared Diamond ponders the chicken/egg relationship of invention to necessity, pointing out that although societies often accord use and relevance to innovations long after they’ve been introduced, the basic instinct to contrive exists outside of this dynamic. Historically, when the artistic and inventive muses congregate around figures brave or confident enough to engage with both of them simultaneously, these individuals seldom shy away from the burdens of living before their time and often seem to relish the friction.

Twentieth-century examples of technological art and its makers are rife with tension: the precarious oscillations of power dynamics that inhabit machine-based artistic production are often the focus of the work itself. A few notable examples: David Rokeby’s uncomfortable early incursions into virtual and surveilled space, such as Very Nervous System (1986–90), parade Rokeby’s anticipatory anxieties as amplified rather than assuaged by their digital medium; the robotics projects of Mark Pauline’s Survival Research Laboratories satirize militaristic and reactionary rage from 1978 to the present with spectacularly violent, self-bludgeoning stand-ins for international superpowers that owe their ironic existence to military technology transfer; and Stelarc’s chilling bodily augmentations, like Third Hand from 1980, which seem to signal an enthusiastic resignation to human obsolescence and our eventual hybridity with machines.

These technologically transcendent fusions, fraught allegories for the Frankensteinian relationship between creator and created, reflect a certain envy of the purported power and omniscience of our invented Gods, and lure us at disfiguring speeds toward precipitous horizons. Italian Futurism had nothing on these guys. But in contrast to Filippo Marinetti’s heated paraphilias (“a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace!”), much of their work feels cold, possibly due to their somewhat detached, dissociated eyes as artists. What then, if Frankenstein’s monster was smarter than his creator, and displayed more humanity? Are we on a collision course with some sort of cyborgian Freaky Friday in the Singularity? Amid all this testosteronal flexing and fusing came Donna Haraway’s 1985 “A Cyborg Manifesto,” a theoretical, refreshingly feminist polemic that described her wildly prescient comfort with technological osmosis, and neatly dismantled its chauvinist primacy.

In the twenty-first century, artist and experimental geographer Trevor Paglen’s relentless inquisitiveness has sucked him into risky and contentious subject matter for most of his career, and his latest AI-generated work, Bloom (2020) — lush, gorgeous, and bizarrely romantic — is no exception. In this series of large-scale photographs of flower-esque forms generated by algorithms trained on images of real-life flowers, he explores artificial intelligence’s capacity to subsume the artist completely, a shadow that’s been hovering about since William Gibson’s “neuromancing” Boxmaker forged its first ersatz Cornell assemblage in Count Zero and kicked humans out of the sublime-slinging business. The implications of Paglen’s new work are imminent: Google’s burly Deep Dream Generator may still be stuck in a tacky, fluorescent-on-black-velvet aesthetic, but it’s only a matter of time until that machine grows a taste bud. In perpetually seeking dominion over nature, humankind seems unable to refrain from destroying our own safety mechanisms. As a good friend of mine once said, “humans have a fetish for course correction” that we indulge at extreme costs. This is nowhere better illustrated than by our ecstatic bond with technology and the power structures it reifies and maintains.

Kenyon is far from the only contemporary artist to wade through this charged conversation, even locally. Currently, Buffalo is also home to artists Paul Vanouse and Stephanie Rothenberg, who both investigate the problematic correlations between human labor, biological ecosystems, and their techno-science counterparts. Vanouse is the Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica award-winning creator of Labor, a wry, intricate, and diabolical-looking project featuring a bioreactor tasked with reproducing the scent and tactile residue of exploitation first shown at the Burchfield Penney Art Center in 2019. Vanouse is also the founder of the Coalesce Center for Biological Art at the University at Buffalo (UB), where he annually mentors three to four artists-in-residence exploring the intersections of art, science, and human vulnerability. Rothenberg founded and co-directs the Platform Social Design Lab, also at UB, to foster socially engaged creative practice. Her stunningly sardonic work concerns itself with the civic fallout endemic to our economies of desire and our embarrassing diminishment by the technologies we so naively thought would connect and elevate us all.

Rothenberg’s and Vanouse’s conclusions often take graceful form while adopting a cool and somewhat castigating tone, whereas the various machines Kenyon devises possess no accusatory fingers, no humanoid avatars, appendages, or frightening anthropomorphisms, but instead seem to extend a warm, benign sort of approachability. That is, until you accept their invitation. In Tap, from 2019, a kitchen sink is embedded vertically into the gallery wall, its spigot spouting a fist-sized ethereal flame that literally does the talking. It’s a neat trick; Kenyon has revived an early industrial relic called an ionophone, a gadget that generates sound waves through an electric arc that acts as a massless radiating element to produce a highly hazardous loudspeaker. The allusion to the biblical burning bush is hard to ignore, but Tap’s somber prophetic emanations all concern the toxic consequences of human-made pollution and misguided resource extraction.

There are six other works in this exhibition, each leveraging a differently sourced technology in its own peculiar and distinct way. Supermajor (2012), possibly the most elegant and economical deployment of techno-magic in the gallery, sets up a real-world special effect: a delightful opportunity for us to argue with our own eyes. In some sense, due to the sheer volume of computer-generated imagery we consume daily, we have become inured to spectacle, so it’s an odd sensation to be entranced by the quiet defiance of physics that Kenyon has orchestrated using a leaking oil can and a strobing LED light. In this “anti-spill,” Kenyon says he is “taking advantage of our observational weak spots” to epitomize the grand illusion of limitlessness we hold when it comes to our patterns of consumption and blithe exploitation of finite resources. Certainly, the various corporate logos on the nine motor oil cans visibly apportion liability to the usual suspects, but there is more than enough culpability to go around. As I stand there, baffled as to how the drops of oil I’m watching do not issue forth from the leaking can but instead undertake an unnerving, quivering climb back up into the cavity from which they should spring, I want to kick myself: I drove my car the short distance to the gallery when my bicycle would have used a source of power that wasn’t stolen or fought over.

Cloud (2013), a device that’s had several iterations before this, generates diaphanous, house-shaped extrusions neatly sliced from a continually rising vat of soap and helium churned to a frothy, but surprisingly dense foam. While previous showings of this work pegged the house-cloud production rate to the local real estate index, this latest version inadvertently references its current locale in a simultaneously hilarious and heartbreaking eulogy to all the beautiful, dilapidated Buffalo houses that have been euthanized by the state. Not since Dennis Maher’s hulking and forlorn Animate Lost/Found Matter (2010): Suspended resonances amid a constellation of assembled residual space from Beyond/In Western New York 2010 has there been a more moving tribute to deceased homes. The second time I visited, Kenyon had moved his contraption outdoors, and the little ghost-houses at first floated up into the crystalline blue sky only to descend back to us in a plaintive and tear-jerking manner, affectionately orbiting us and disintegrating as we watched.

The House is a recurring symbol in Kenyon’s work. With this year’s Tide, Kenyon literalizes the twin lethalities of “underwater” mortgages and climate change by submerging several hundred tiny, house-shaped effigies in a spectacular pyramid of champagne glasses. Invoking both Ponzi schemes and wedding celebrations while also alluding to the monumental constructions that only slaves could have built, the work has a tragic, ineffable grandeur. The little houses, cast from a transparent polymer possessing the same refractive index as water, are plopped awkwardly into the empty glasses awaiting their inevitable deluging and disappearance, like Dorothy’s house in Oz. Spurred by live updates in foreclosure and eviction data, invisible machinery drips crocodile tears from the ceiling in a grim, silent, slow-moving pantomime of Noah’s flood. As the glasses gradually fill, the most vulnerable houses on the periphery are rendered invisible in their splendid, watery graves. There is no deus ex machina here, no ark; only force majeure, that slippery bitch of a clause conveniently absolving the insurance companies of their liability.

The last two works are even more quietly devastating. The first, Lockset (2020), appears to be the only work in the gallery devoid of machinery, until you realize that an old technology is conspicuous through its absence: only the keys are present, hung unceremoniously on the wall. The locks they once opened are now sealed against their former denizens, tenants evicted from their residences due to desperate circumstances. Next to the more audacious works in the show, this one seems oddly diffident until you realize that each key’s jagged edge casts a small shadow of its owner’s profile on the wall. The locks have been re-keyed (by Kenyon himself, who learned locksmithing for the project) to embed subversively and permanently their tenants’ identities into the physical lives of their former homes. It’s probably a more subtle and sentimental act of defiance than the landlords it indicts could ever appreciate, but that only serves to underscore the brutality of the system that demands it.

The final work is a new iteration of Kenyon’s Notepad project (2007–present), in which he and designer Douglas Easterly microprinted the full names, dates, and locations of every single Iraqi civilian death on record for the first three years of the Iraq War, appearing to the naked eye as twenty-six ordinary blue rule lines on a standard-sized yellow legal pad. A limited edition of one hundred of these pads was distributed to members of the United States Senate and House of Representatives as a clandestine act of protest and commemoration: when used, the sheets with their hidden data were then entered into the Congressional Record and archived in the Library of Congress. This work won its authors international recognition, culminating in Kenyon’s 2015 TED fellowship, and is included in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Kenyon’s new version, Alternative Rule, enumerates every child killed by gun violence in the United States since the Columbine High School massacre. This time, the microscopic lines of text trace the kind of horizontal wide-ruled sheet that is often used by first and second graders to practice their penmanship. We are invited to move a wireless transmitting endoscope lens over the surface of the innocuous-looking paper set on a small school desk; the lens projects an image of the names of over a thousand murdered children on the adjacent wall. It is a difficult pill to swallow past the lump in one’s throat.

Each of Kenyon’s inventions possesses a curious signpost-on-the-way-to-doom quality. Cairn-like, the works in The Wolf at the Door are memorials along the path to erasure: financially eviscerated renters, hapless homeowners, colonized societies “relieved” of their resources, victims of violence so numerous that their names form the very substrates onto which the names of even more dead can be inscribed. Upon returning home, I cried for half an hour and felt haunted enough that I was compelled to return twice, as if pulled by a tractor beam. A last inadvertent bit of technology, perhaps.

What a fitting coup de grâce.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Haunted by Burden

(Appeared in Sept 19, 2016 issue of The Public)

Torn Space’s Burden

Performed August 18-21, 2016

Silo City, Buffalo

“True art, when it happens to us, challenges the ‘I’ that we are. A love-parallel would be just; falling in love challenges the reality to which we lay claim, part of the pleasure of love and part of its terror, is the world turned upside down.”

—Jeanette Winterson, Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery

As both an artist and a deeply emotional human, I am no stranger to having my soul ripped out of my eyes and stuffed back in, and I have spent long exquisite hours in a multitude of museums staring slack-jawed at works that left me breathless and teary-eyed. I once even started sobbing in the presence of Anselm Kiefer’s Buch mit Flügeln, prompting my friend Heather to whisper to the concerned curatorial assistant guiding us through the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, “She’s okay. She’s just very passionate.”

Passion is what keeps us going. Art, with a capital A, makes difficult demands of its channels, rendering us at times unfit, unfed, and unsteady as it extracts its toll, and there is no escape once you’ve surrendered to it. Passion is what enables us to continue loving Art even though it asks the impossible of us.

Art mates for Life.

In light of this, finding human partners with whom to travel this potholed passage can be a challenge. Often, another artist is the only option. After all, you share a mistress. Melissa Meola and Dan Shanahan, the founders of Torn Space Theater, live in such a ménage á trois. Their remarkable company’s recent production, Burden, is the 12th original fruit of that union.

Three weeks ago, while attending an early Sunday evening performance with my adolescent daughter, something strange happened to me. Trying to figure out exactly what that was has become a little game I play with myself in my brief moments of downtime. My memory of the show is nestled so snugly in my mind that nothing short of protracted work-related panic dislodges it, and I’ve come to accept and appreciate the flashes and snippets of it that invade at odd, unbidden moments.

Near as I can figure, I experienced a brief bout of Stendhal Syndrome, a psychosomatic disorder that causes certain atypical physiological responses in reaction to viewing art. In plain English, I was so moved I almost passed out.

Staged at Marine A, the vast abandoned grain elevator complex dominating Silo City, Burden is both an ode to the albatross, and a eulogy for the dream of ease. The audience is gently herded by silent docents through a David Lynchian juxtaposition of tableaux haunting the concrete labyrinth. Each station is a phantasm immersed in emotions, pantomimes of heartbreak and frustration, punctuated and augmented by sound and music so skillfully deployed it seems to come from within our own heads.

Torn Space’s inclusive, intersectional ensemble of performers, a gorgeous and full panoply of talents unto themselves, renders these fragments with exquisite skill as they capture and convey a full spectrum of experience, each contributing their slice of perspective to what begins to emerge as a collective cry for relief in the face of a world gone mad: The gentle ministrations of an overwhelmed caregiver to a dying burn victim, the aria sung by a dethroned empress, Gershwin rendered through a single soulful trumpet as if it was ‘Taps,’ graceful black athletes in blinding tennis whites consigned to the ignominy of the media’s condescension, a mature melancholy diva imprisoned by obscurity, the yearning glamorous ghosts of Ziegfeld dancers, star-crossed lovers, doomed crooners and disillusioned preachers all conspire to pull you into a dizzying Purgatory masquerading as Paradise.

Left to our own devices for brief periods, fortified by the occasional cup of wine, we meander through these tattered traces of random highlights pilfered from overlooked lives. Punctured by gorgeous spectral light and video installations by Carlie Todoro-Rickus and Brian Milbrand that indict memory for its faulty fragility, the darkness and weight of time and history is upon us, embodied not only by the looming concrete hulk above our heads, but by the massive rusting steel hull of the SS Columbia moored to its docks: a 114-year-old relic of the steamboat age, the first such vessel to be equipped with a ballroom.

It is in this ballroom that I finally lose my composure.

During the penultimate scene, a lament, sung with aching and delicate tenderness belying the stature of its formidably fluid chanteuse, Lilac Wine is a paean to oblivion, a conflicted entreaty to indifferent gods: grant me the grace to forget the unforgettable.

The hot pink light on the stage, the glittering sequins of the dazzling costumes, and the periwinkle sky outside all fuse psychedelically, and I swoon for a long, disorienting moment. Shaken, my daughter and I are gently thrust out into the glory of a tent revival, replete with brass band serenading a setting sun that looks like something straight out of a Turner painting. The Preacher howls about rebirth and I am wrecked. Through my tears, I look up at the blurred, worried face of my daughter who cradles my cheeks with concern.

“It’s okay, sweetie.” I say. “I’m just very passionate. And this is what Art is supposed to do.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

ANNE MUNTGES:

Skewed Perspectives

(2015)

Anne’s World…

(Catalogue Essay)

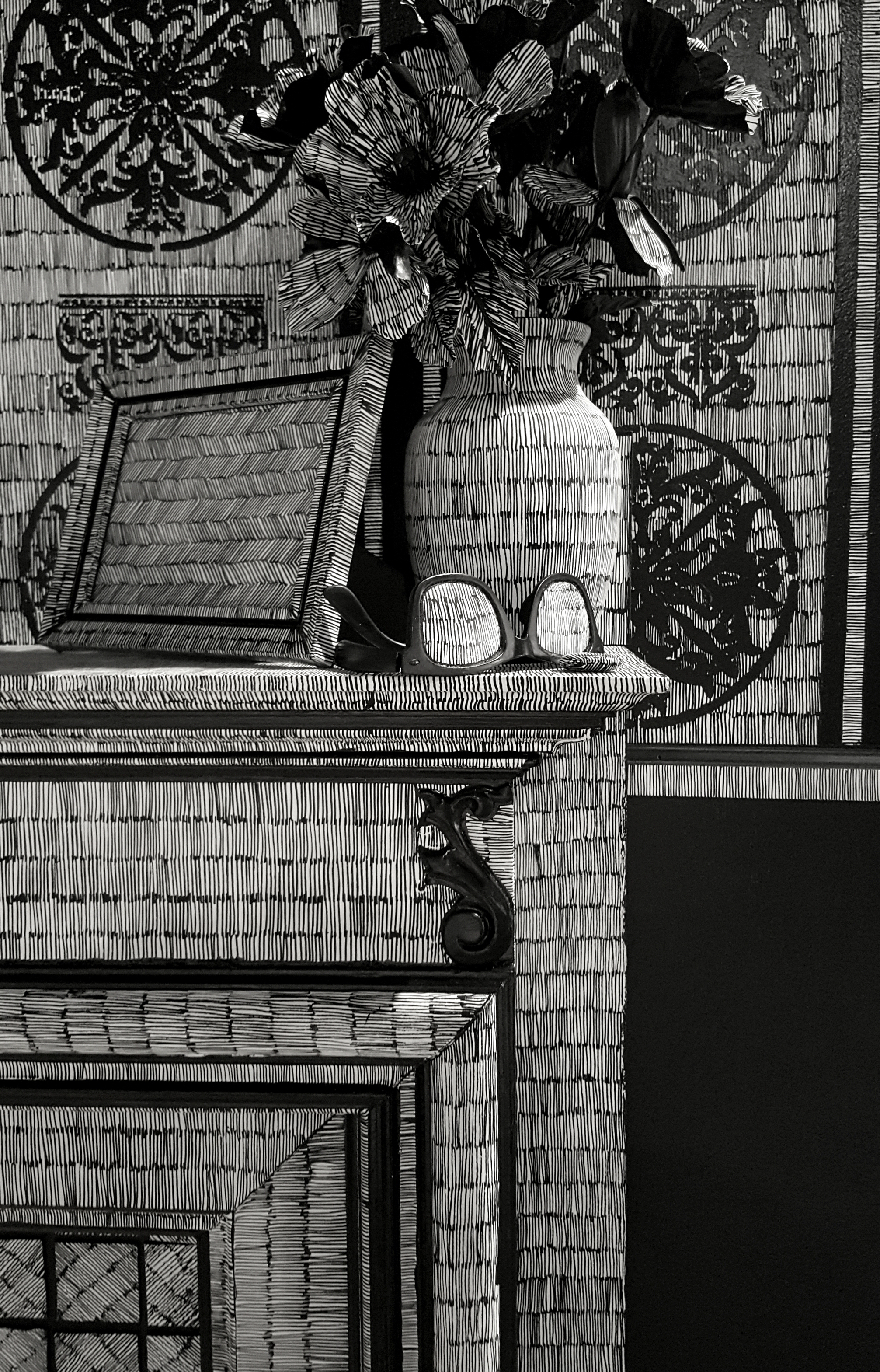

It’s a curious and powerful thing to make one’s mark upon the world. Childhood scribbles are our first evidence of agency. We exist! We can change things! All we need is forty-five seconds left unattended with a crayon and an empty wall. The ensuing rush of parental yelling and gesticulating quickly introduces us to the consequences of our discovery: mark-making has power.

For most of us, our scrawls are eventually socialized and gradually distanced from that original primal act of authorship. So few of us retain the thrill of that initial realization that we can create, from humble materials, not only a trace of our presence and passing, but an entire world where anything is possible. When the tendency to conflate the real with the imaginary persists into adulthood, we label it as an eccentricity at best, and at worst, a pathology to be rooted out and extinguished, lest its bearer infect the world around them with their wild phantasms. Except in the case of the artist. The artist’s job is to train her mind to misbehave, and to assert her inalienable right to keep drawing on the walls.

Like many of us, Anne Muntges grew up reading the classic children’s book Harold and the Purple Crayon, and remembers Harold trailing his crayon on the wall beside him in one long continuous line as he decides to set off on his moonlight walk. In the story, Harold’s big purple crayon becomes nothing less than a magician’s wand, calling up moons, dragons, oceans and cities, until he gets tired and draws his own bed in his own room, falls asleep in it, and drops his magical crayon to the floor, ending the story.

In Skewed Perspectives, Muntges has conjured a full and complete Room of Her Own: a perfect, inhabitable drawing in scrupulous detail, the ultimate expression of the inscribed made real. By creating a completely immersive environment built solely from line, she lays claim to the dimensional world by insisting that its realness be contingent on her graphic assent. Muntges performs magic with her little black wand, and she knows it. Resurrecting objects and architecture by inscribing them with her exhaustive incantations, each tiny hatch mark is a titch in time, a small vertical line counting off bits of her ultimate currency, minute offerings to the cosmos in exchange for her divine power to imbue inanimate objects with new life.

There is a certain quixotic charm to this utter embrace of surface. Perhaps Muntges is conscious of the tensions that strain our thin veneer of reality, and endeavors to strengthen its meniscus with her mark-making, lest the underlying chaos of the universe escape. As a result, her work presents less as a capitulation to the reductive notion that women exist to decorate, (in both the passive and active sense) and more as an assertion that the skin of the world requires a fierce and disciplined custodian.

To Anne Muntges, an object is not real until she has drawn it from the coals and forged it with her inky black refiner’s fire, and the vertigo one experiences in their presence is not an accident. It is a rare privilege to stand teetering in a portal between worlds, but be careful and hold on to the doorjamb. Muntges’ mischievous grin might be last thing you see before she pushes you through.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

ETERNAL EMISSIONS

The Work of Dana Tyrrell

(2015)

(Originally published in “we are / what grows here / no longer: 2015 University at Buffalo Master of Fine Arts Thesis Publication.”)

Clinically, the cock, that fleshy protrusion nestled awkwardly into the primary forking of half the world’s human bodies, primed to engorged capacity through a convoluted wave of minuscule electrical impulses, rises to attention in a sort of salute, a hapless gesture made in defiance of mortality. Its pump-like primary functions: the elimination of liquid waste and the ejection of liquid fertilizer. Hardly the romantic implement extolled in terms both endearing and repugnant in centuries upon centuries of art and literature. A fickle and rebellious organ, the cock, like a reckless relative given to boisterous and inopportune shouts during somber family gatherings, a stout little arm shaking its recalcitrant fist at the unjust world that ceases to exist upon the death of its every bearer, exploding in a shower of virility before succumbing to ignominious shrinkage.

Sexual organs, partnered in proximity to their corporeal sibling, the anus, together perform the indispensable physical function of expulsion, the ultimate biological act of which a given body is capable. Two of the three substances produced remove its toxins, and the third attempts to ensure its owner’s immortality: the organism must not perish without issue.

In a queer framework, this presents a quandary. Humans are, regardless of station, sex or school of thought, expected to produce something. That which we produce stands in our stead upon our eventual expiry, and in a heteronormative culture, the culmination of this drive to propagate results in small squirming inchoate copies of ourselves, utterly at the mercy of our indulgences, whims and weaknesses. When breeding is the preferred mode of production, the remainder of life is spent shepherding these helpless creatures through to their own ultimate moments of self-replication, and the strangely futile cycle continues. Abandonment of these particular manifestations of biological imperative is not permissible, lest we suffer the ostracizing consequences.

Shit and piss, on the other hand, relegated to trenches and holes, buried and denied, flushed away and ingeniously repudiated (plumbing!), are no less our issuances, borne of our most basic ruminative functions. But these represent that which must be eliminated: the evidence of the passing of all things into dirt. Reeking with the stench of decay, our excretions are unpleasant reminders of Thanatos, and we seldom hold them up as accomplishments, the occasional toilet-clogging epic turd with beer-can-like proportions excepted.

In order to refuse Thanatos its due, we look to Eros for an affirmation of life, but society tends to conflate the sexual act with its occasional byproduct, ascribing a confinement of purpose to the sensual body, and condemning acts that fall outside the purview of procreation. In a largely religious society that legitimizes and privileges heterosexuality, the only acceptable claims to eternal life are progeny and piety, but those descendants, bearing the brunt of the outsized expectations we place upon our notions of immortality, rarely live up to the task. Our progeny are carriers of our genetic information only, and become stubbornly committed to the ridiculous notion that they are their own persons with their own lives, and not simply extensions of us, meant to exist as our proxies through time. Children make poor monuments, as anyone who’s ever attempted to make one sit still can attest. But woe unto you, should you have the temerity to assert the inadequacy of their posterity.

If one is truly committed to ensuring one’s own individual immortality, offspring of a less biological nature present a far safer bet: Art works well in this capacity, as does architecture, creations with no agendas of their own, repositories of our ambitions and abjections, places to house our hopes and shed our shit. The very impulse to place one stone atop another is as inexorable as the one that impels our next breath, a need as deep-seated as sexual release, albeit a tad less dramatic. We enshrine our selves in every material we affect and alter, and the often grandiose objects that result contain a record of our passing, receptacles for our more intangible secretions: our thoughts, dreams, nightmares and identities.

In this sense, Art queers Thanatos. Art is an oppositional act, a disregard of death in the face of its absolute inevitability, and a celebration of that scorn. Art queers death, if only in the mind of its maker, which, sometimes, is enough. It is the Mind that truly matters, anyway: that which we are most likely to identify and define as the true self, the inexplicable cohesion of biology into a unique consciousness, and the concurrent unanswerable questions that poses. We are impossible lights, carried in perishable vessels that dissolve over time into misshapen lumps of browning organic matter, ultimately resembling nothing so much as the shit we used all that ingenuity to flush away.

In 2010, the sculptor Ken Price discontinued his treatment for cancer in order to secure his position in the pantheon of Art History by creating one last group of works for his retrospective at LACMA, a show he learned would eventually travel to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The convoluted ceramic pieces, described in the catalogue by critic Dave Hickey as residing “on the line between bewitching and ludicrous,” were dirty ditties to the flesh: amorphous, alternately priapic, vulvic and scatological bulges of sheer exuberance, a brightly-colored parade of lascivious appendages and ejaculations, strutting into destiny. Price’s last act in life was to immortalize his vision, and his every piece was a testament to the laconic humor with which he faced his impending demise and the gratitude he felt in being able to make them.

Dana Tyrrell’s wonderful works take up Price’s colorful banner, and march forth holding it with the steely, dazzling resolve of a veteran drag queen fronting a Pride parade. Reified toxic substances spewed gleefully from pressurized canisters, they are literal eternal emissions, glorious hybrids of petrified shit and come, evocative of enormous paleontological poops transformed into semi-precious stone through the alchemy of time.

Moving through the offerings, one gets a sense of ramping up. The quiet set of paintings, Untitled (Forget Your Bones) sets the stage for the rollicking headliners that follow, and call to mind the naked terrain of a doyenne’s complicated face first sitting down at the mirror, makeup brush in hand.

Untitled (Eternal Thirst), a wry allusion to the evangelical Christian notion of ‘The Rapture,’ posits a failed ascension, the former wearer of the battered oxfords having been, in lieu of a glorious homecoming, reduced to a creamy slurpee-like substance in a fleshy caucasian shade of taupe. An unfortunate regression, perhaps, to an invertebrate state, not given to complex critical thinking.

Evocative of the reactionary horror flicks of the 1950’s, when this country’s accumulated fears of nuclear annihilation at the hands of a the godless Communist hordes metastasized into visions of insatiable glowing blobs that devoured entire towns, Landslideand Untitled Pink Blob take up where the forlorn shoes leave off, the apocalypse elapsed, the dams of belief all broken and its idols drowned, yielding huge, wet, glistening, boldly miscegenated fungi, so vibrant and alive that you watch them carefully for the telltale contractions of breathing.

Marvelously, the mylar-encrusted Sweet Nothings come together to form the denouement. With this chorus line of psychedelic psilocybin turd blossoms, Tyrrell has produced glittering paeans to our ultimate abjection: excremental extrusions, gussied up in teeth-numbing shades of fluorescing brilliance, reflectively glinting in the plunging sun, and proclaiming victory in defiance of that long, looming night.

All images copyright Dana Tyrrell, Jr.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

FRANCIS BACON: God Killer

(2011)

In James Morrow’s 1995 novel, Towing Jehovah, God’s two-mile-long body is discovered floating in the Atlantic Ocean. The ‘Corpus Dei’ is to be transported to its final resting place in the Arctic by the disgraced captain of a doomed supertanker, a miserable man named Anthony Van Horne, who has been drowning in futile ablutions in an effort to cleanse himself of the guilt of having caused the greatest environmental disaster of all time. The assembled team tasked with this gruesome attempt at cryogenic preservation falls prey to an ecstatic despair as the implications of their mission sink in:

There is no God. But there was one, once.

These simultaneous certainties foment madness in the characters, suddenly releasing them from the bonds of the social contracts on which they have depended their entire lives. A non-contingent universe has claimed them. What choice do they have but to fall to orgiastic wretchedness?

In 1945, Francis Bacon, an unwieldy and brutish, but simultaneously convivial man haunted by his own transgressive desires and ill-equipped to ply trades any less bruising than that of a painter, finally gives into his ecstatic despair and announces the death of God with his solemn triptych, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion at the Lefevre Gallery in London. The work was widely regarded to be an assault on the senses and sensibilities of what up to that point, had been a rather genteel and conservative art-viewing public content with the sly elliptical allusions to the nihilism that had dominated recent history, Abstract Expressionism and consequently, contemporary art at the time.

In Bacon’s depiction of the Passion Play, the grotesque figures represent Alecto, Megaera and Tisiphone, the Furies of Greek mythology, creatures tasked with the retribution for crimes that exceed the capacity of human justice. Their portraits, however, are nothing short of elaborately colored cartoon depictions of disembodied penises and their appended scrotal sacs squawking through twisted miniature mouths like hungry baby birds, plunging the thematic discourse of the piece into near-pornographic abjection. The punished and the punishers are united in bestial deformity. It was a blasphemy that the current world temperament embraced with tightly shut and tearing eyes.

Bacon is credited with oft repeating the line, “You can’t be more horrific than life itself.” A pithy epigram, no doubt, and one that leaves little doubt as to the personal certainty with which Bacon pronounced it. His paintings bear witness to the fact that the horrors to which he referred were not simply those atrocities to which the world had recently been subjected, but his own determinative experiences as well.

As magnanimous as he was with the press and his biographers with the details of his rather pathological life, he was famously elusive when it came to the outright explanations of the inspirations for his startling work. Perhaps he feared redundancy, as it wouldn’t have been possible for him to scream in anguish more loudly or eloquently than he did in the paintings themselves, though he did say that “The job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery…If you can talk about it, why paint it?’” This quote could reasonably lead one to surmise that he was, in fact, incapable of speaking of the hideous events that befell him. That he continued to plumb the same subject matter over the length of his career may attest to the indelibility of the marks left on him.

The revelation that he’d been whipped repeatedly and savagely as a child at the behest of his horse-trainer father by Irish grooms with whom he eventually came to have sex would be more than enough to create a psycho-sexual schism in a young boy’s mind, but as his delicacy and asthma made normal life next to impossible, he was also tutored by clergymen at home. Given what we know of the Catholic church’s predilection for turning a blind eye to an astonishing array of abuses perpetrated by its ambassadors, it would not be outside the bounds of plausibility to surmise that Bacon may have also been abused by the very trusted and religious men tasked with his tutoring. His many self-portraits conjure the stunted and incomplete appendages of thalidomide babies, with their truncated sensory apparati, perhaps incapable of experiencing the nuances of gentle touch so particular to their nonexistent fingertips.

It is conjecture, to be sure, but a violation of himself when not yet fully formed, an interruption in the ‘normal development’ of a human being, could easily have given rise to what he may have perceived as a deformity in his soul, the cruel joke of course being that he may have come to the conclusion that he had no soul, as any trust in God would need to be a hardy plant indeed to survive such a trampling.

Bacon’s possibly retaliative ‘screaming popes’ are reminiscent of the grainy black and white images of capital punishment administered by electric chair when such things were still made public. The clenched knuckles, the taught horror, the rictus grins of orgasm overlayed on a substrate of decay and putrefaction. In these paintings, Bacon has consigned the Bishop of Rome, the paternal head of an institution whose minions may have been partially responsible for his own tortures, to a perpetual hell. In obsessively repeating the effort, he seems to have been trying to capture the apotheosis of agony, unsatisfied with anything less on the face of what he considered the ultimate symbol of his tormentors: The Father, Who Art Not in Heaven.

There are, according to some, a total of forty-five pieces depicting Bacon’s various approaches to his recontextualized pontiffs, and eight major works, beginning with his “Head VI” in 1949, and climaxing with his Study after Velasquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X in 1953, a stunning juxtaposition of Velazquez’s original 1650 portrait, Titian’s Portrait of Cardinal Filippo Archinto from 1558, and the infamous still of the old woman shot through her spectacles from Sergei Eisenstein’s seminal film The Battleship Potemkin. Effectively, Bacon had created a proto-mash-up, and his habit of image appropriation would continue for the rest of his career.

The name of the subject of the original Velasquez painting which so captivated him, “Pope Innocent X,” seems a savagely ironic jest. He may or may not have been aware of the X-certificate that had been just established by the British Board of Film Censors in 1951, to designate films that were deemed unsuitable for children under the age of sixteen, but the “Innocent” moniker would have been sure to grimly amuse him.

In many of these pictures, Bacon’s possible equation of himself with the included slabs of meat cannot go unnoticed. The meat is pig (bacon) and lamb simultaneously, and the allusion is the same: the artist depicts himself as a sacrificial creature, already disemboweled, a raw and bloodied offering to an uncaring, insatiable void, a vicious maw that unceasingly continued to consume him as he aged.

His first lover, a sadistic, alcoholic ex-Royal Air Force pilot named Peter Lacy, was known to regularly destroy the artist’s paintings, and beat him mercilessly, leaving him wandering the streets of Tangier half-conscious. It was a relationship which he maintained through his forties, openly in embrace of all the brutality it entailed, all the while ingesting the attentive drama as nourishment, a toxic kind that cannibalizes the organism it is thought to feed.

In Existentialism: A Reconstruction, David E. Cooper offers an over-simplification of the philosophy as a way to explicate how it may have been so widely embraced as a personal ethos for those whose alienation and despair demanded a banner under which to rally: “Existentialism was a philosophy born out of the Angst of post-war Europe, out of a loss of faith in the ideals of progress, reason and science which had led to Dresden and Auschwitz. If not only God, but reason and objective value are dead, then man is abandoned in an absurd and alien world. The philosophy for man in this “age of distress” must be a subjective, personal one. A person’s remaining hope is to return to his “inner self”, and to live in whatever ways he feels are true to that self. The hero for this age, the existentialist hero, lives totally free from the constraints of discredited traditions, and commits himself unreservedly to the demands of his inner, authentic being. ”

Bacon described himself time and again as “an optimist, but about nothing.” And towards the end of his surprisingly long life, declared, “we live, we die, and that’s it.”

This unmistakably existential bent, saddled with its concurrent elusive mandate of living authentically, and coupled with the fetishization of Bacon’s own pathology, meant that he had no choice but to utterly capitulate to the demands that such a worldview—and his inner, authentic self—place upon him. If these demands ironically called for his physical annihilation at the hands of others, so be it. It would only constitute his logical and committed pursuit of the true nature of existence: that it is most clearly defined by the consistent and constant threat of non-existence.

His passionate embrace of what must have seemed to many a self-destructive lifestyle may simply have been an intrinsic understanding of this pitiable view of the human condition, and a determination to be the fully culpable author of his life, and certainly not one lived in bad faith. Being as well-read as he was, it is doubtful that Bacon spent his life ignorant of the major works of the Existentialists, and as he was reputed to have been a great admirer of Samuel Beckett, a writer certainly emblematic of the movement, and defined by his own portraiture of the nature of futility.

One could infer from Bacon’s consistent use of religious iconography, that he was also engaged in a sort of Visual Theodicy, attempting to reconcile the existence of evil with his inexplicably divine ability to render it. In 1988, Bacon reiterated the painting that had brought him to acclaim, with Second Version of Triptych 1944, a refinement of his Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. In this more elegant version, his original vision solidifies, its surface a smoother and less porous rendition of the avenging Furies, as if their armor had been reworked to weather the ever more diabolical crimes that they must punish.

Bacon, seeing himself perhaps as their agent, having dispatched them in the first place, conveys an almost hysterical level of chromatic glee in the Second Version, as if maybe his improved technique in their rendering would make them more capable of finishing the job he sent them to do 44 years before.

Gilles Deleuze, in his book, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, says in his introduction, “What we are suggesting in effect, is that there is a special relation between painting and hysteria. It is very simple. Painting directly attempts to release the presences beneath representation, beyond representation. The color system itself is a system of direct action on the nervous system. This is not a hysteria of the painter, but a hysteria of painting. With painting, hysteria becomes art. Or rather, with the painter, hysteria becomes painting. It must also be said that the painter is not hysterical, in the sense of a negation in negative theology. Abjection becomes splendor, the horror of life becomes a very pure and very intense life.”

God is not quite dead yet. He annoyingly persists, in ever more counterfeit forms. He must be eradicated. The comfort he provides is a lie. He is guilty of the ultimate crime against man: Hope.

Bacon’s twisting and grotesque forms embody the perpetual anguish of false hope, and were compared to the similarly distorted imagery that the Surrealists were producing at the time. But, dismissing the label of “Surrealist,” Bacon’s series of paintings based on The Oresteia made his point, asking as to whether there was anything “more surreal than Aeschylus?” the two-thousand-year-old Greek author whose trilogy was based on the fraught, bloody and violent lives and deaths of the family of Agamemnon.

Phenomenologically, there was no place for Bacon to position himself other than to give himself the label of “realist,” as his vision did not allow for the notion of the real as anything other than the authentic multi-perspectival depiction of the horror of existence robbed of the diaphanous and deceptive veil of religion and its concomitant reliance on manufactured meaning. Bacon’s reliance on the triptych form and his literal smearing of the paint itself reinforces this fractured and hallucinatory indictment of his subjects. They are akin to mugshots of both personal and human history, a multiplicity of views meant to create dimensional, ontological soundings of the depths to which human beings can sink. Hence, all theology chokes on the coagulated blood of his butchered evidence.

His utter concentration on the flesh further reinforces this idea: the body, one’s body, the flesh of the subject containing the only mechanisms by which the object can be apprehended, is all, really, that exists. The flesh is our clock, the living proof of our presence, and as such, defies any and all attempts to define it as a fixed object. It is decaying, changing constantly, not only ever in motion, but ever in degeneration and dissolution. It is, in effect, its own Corpus Dei. There is no God but the one contained and created in the flesh of the self, and as the self is a vulnerable and ever-deteriorating vessel subject to the most humiliating degredations by the vessels of other Gods, the playing field is level. There cannot be an immortal, singular and omnipotent ‘God’ that supercedes all other Gods. The very mortal nature of the vessels which contain and perpetuate the myth of his existence are proof of its fallacy. The body is all that is, and all that will ever be.

When observing them directly, in person, the paintings themselves are never quite at rest in their frames, even the small ones. They are figures trapped within their own vibrations, on surfaces which seem ill-equipped to contain their frenetic shuddering. It’s as if Bacon’s paintbrush is capable only of the slow shutterspeed endemic to view cameras at the turn of the last century. His canvas is a slow film, capable of registering the faintest pulses of even the most extreme spectrums of light. They are infra-red readings of the inner pulses of life, x-rays of the desolate and hardened cage on which the flesh hangs, trembling fingers gripping onto the crumbling ledges of life.

When you close your eyes, they let go.

And suddenly, you are tempted to do the same thing.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

ON THE DIONYSIAN DIVINITY OF REBECCA HORN

(2011)

As evidenced by early drawings (fig A), Rebecca Horn has always been concerned with the body’s interiority and import. But, in 1968, her honor besmirched by an unprovoked attack on her corporeal sovereignty, Rebecca Horn began jousting with the heavens.

Enlisting a small circle of friends, and painstakingly training them to use the formidable arsenal she builds, she tells and re-tells of mythic ancient battles in Scheherazadian fashion, embellishing the story of her own defiant triumph over isolation, loss and loneliness, and in the process, deferring Death’s interest in her one more day.

At the age of twenty, after rebelling against her conservative parents and spending a year at the Hamburg Academy of Fine Arts, Horn contracted a severe lung infection from the fiberglass she had been working with and found herself confined to a hospital for a year, during which time both her parents died, leaving her in utter and complete devastation.

Having been forced to shun her native German and learn French and English during the linguistic splintering of post-WWII German education, Rebecca began drawing as a child in order to circumvent spoken language, and was encouraged in this by her Romanian governess. As a result, there resides a curious form of multi-lingual eponymy in much of Horn’s work, which may be a clue to her disposition, and an indication that despite the seriousness of her intent, she is not without a sense of humor. Vocabulary and language are very much at play here, and she begins her canon with a riff on one of the most fundamental aspects of her identity: her name.

Unicorn (Einhorn), 1971

In a “glimmerous” heat

Out of a cradled field

a little white tip

points in your general direction

When I first saw her on the street, walking by—(me, dreaming my own “unicornian” dreams)—her strange rhythm, one step in front of the next…

All was like an echo-shock of my own imagination. Her movements, a flexibility: (knowing how to use the legs entirely), but the rest of her: frozen in ice, from head to hips, and back again.

Drinking coffee, talking politics and me, (how to express to a person, ready to marry at twenty-one and buying with all her money a bedroom set, my own beliefs in life?)—And the complications and explanations, that I did wish to build a certain instrument, a stick made “only” out of wood, for her own head, to pinnacle her way of walking.

Next weeks, finding right proportions, body weights and object heights, distances and balances…

The performance took place in early morning—still damp, intensely bright—the sun more challenging than any audience, creating a phenomenon around her…

Her consciousness electrically impassioned; nothing could stop her trancelike journey: in comparison with every tree and cloud in sight…

And the blossoming wheat caressing her hips, but not her empty shoulders.

Inviting comparison to Frida Kahlo’s Broken Column — another artist whose frustrating lifelong struggles with an adversary body informed her work — Unicorn (figure 1, ) (figure 2) from 1971 confronts us with the initial instrument with which Horn will pierce the veil, tearing the hole through which she will re-enter the sensual world. Following from the premise that a subtracted sense lends the power of its absence to strengthening another, Horn turns the equation on its head, quite literally. Through augmenting one faculty, another will falter, but which? As Unicorn fortifies the divinity of its wearer, so it precludes her from full physical articulation, its straps and harness a near-exact echo of Frida Kahlo’s imprisoning brace.

Images such as these function in Horn’s work as symbols of the liminal spaces between bondage and bandage, and are essential aspects of the principles to which the theorist Herbert Marcuse refers when he expounds on the societal constriction of sensual opportunity, and the resultant narrowing of erotic focus in his book One Dimensional Man. But Marcuse’s bleak vision of a technologically rationalized civilization finds itself both vividly illustrated and then subsequently refuted by much of Horn’s oeuvre. With Unicorn, she has begun to form an iterative model of her own Great Refusal, summoning the power of Eros in this pursuit, and resurrecting the utopian vision expressed by Marcuse in his earlier book, Eros & Civilization. Evidenced by the poem above, the epiphany she seems to have experienced with the execution of this piece and its performance laid the groundwork for a lifelong practice. From here on in, her work would consist of an endless tactile expansion, not a contraction, and her experiments to this end would be moving testaments to her belief in the power and importance of touch. Touch is central. Touch, in the beginning, is everything.

Much as a child affixes paperclips to the tips of the fingers in order to shift and modulate their sensitivity, Rebecca Horn extends her hands beyond their natural limits in Finger Gloves (figure 3) from 1972. She is deliberately regressing here, actively seeking the nascent pleasures and sensations rooted in childhood and infancy. In an attempt to reclaim some measure of Freud’s primary narcissism, and thereby re-birth herself, Horn’s every piece stands as an entreaty to sensual restoration: she will assault the waiting world with a punctuated openness — inventing and contriving objects, garments, films, performances and poems that will enable her, and consequently us, to touch, absorb, pierce, yield to, consume and digest the skin of the world in a process of psychic peristalsis. Assuming the guise of Eve, that mythical protean woman, that original naïf, she will tempt the viewer into joining her in complicit curiosity. In her company, no apple will be left untasted.

Gingerly testing the tensions between opposing forces, stances and emotions, Horn stalks the boundary illustrated in Touching the Walls with Two Hands Simultaneously, 1974, (fig 4) between possible attitudes, never lingering for long on one side or the other, rather, performing exercises in straddling extremes. It is akin to an invocation, a meticulously choreographed rain dance aimed at precipitating a turbulent sea inside the viewer’s eye with subtle movements. Nothing of Horn’s work speaks of the grandiose, rather, she prefers augmentation of the senses through the amplification of diminutive gestures, and concentrates her careful eye on the impetus for movement, and its relationship to the larger spaces those gestures inscribe. This entire endeavor is aimed at the reclamation of the moment she found herself the victim of the grandest of larcenies: the theft of her time through the abduction and subsequent clinical incarceration of her body.

That her deep artistic embrace of total sensory perception would result directly from a yearlong encounter with alienation and deprivation may be a presumption, but one holds out hope that such a Marcusian level of sensual engagement with the world would be possible without such a violent incitement. The assertion that female artists often find themselves pigeonholed by the pathology that informs their work is not without merit, but in Horn’s case, her pathology is not unique to her, or to her sex. I would argue that the vulnerabilities which existed for her, exist for us all, regardless of station, and as such, her memory of them permits an unusual level of universality in her conveyance, despite her wry and oblique feminist leanings. I would further argue that her resultant access to that underlying commonality is not a hindrance but a privilege, and not one granted her, but one that she has cut for herself from the cloth of a male-dominated art world. It is her fluency in visceral language, one that is commonly spoken in the sinews of all humans, that enables her to strike the resonances that set her work apart.

In a review of her 1993 solo show at the Guggenheim Museum, Robert Hughes wrote:

“The work of the German artist Rebecca Horn, on view at New York City’s Guggenheim Museum through Oct. 1, has something in common with recent American feminist art, but not much. You could call hers a European sensibility, meaning that it is open to nuance and, whatever its references to the politics of the suffering body, to humor. It is oblique, magical and ironic, and has none of the in-your-face tone of complaint (men are colonizing thugs, women are victims, and a display of wounds is all you need to make a piece of art) that renders the work of so many of her transatlantic sisters so monotonous. Its one point of similarity with feminist art is that it is grounded in trauma.”

Regardless of whether the art establishment is guilty of condescendingly granting a certain leeway to women artists by way of the exploitation of their pathologies, it has unwittingly created enough room for them to create more daring work; work, which, in the artist Jenny Holzer’s estimation, has collectively become the more challenging contribution to contemporary art, by virtue of its willingness to extremity. Lucy Lippard foretold this in 1976 when she wrote of how women were seizing control of what had been previously viewed as vulgar, picking it apart and constructing new dialogues.

Horn’s fetishization of her own pathologies, ie., her fear of flying, claustrophobia, reluctance to wear gloves, is an act of bravery, a deliberate recapitulation, a refusal of surrender to hysteria, and hence, a therapeutic device. That valor in the face of anxiety, in the face of the truth of memory, would deny us the facile dismissal of her gender’s role in her art, requiring us to look deeper, past her sex, into psychological territories that unite us all. In his landmark text “Eros and Civilization,” Marcuse describes the way in which memory may reward those brave enough to explore it fully:

“If memory moves into the center of psychoanalysis as a decisive mode of cognition, this is far more than a therapeutic device; the therapeutic role of memory derives from the truth value of memory. Its truth value lies in the specific function of memory to preserve promises and potentialities which are betrayed and even outlawed by the mature civilized individual, but which had once been fulfilled in his dim past and which are never entirely forgotten. The reality principle restrains the cognitive function of memory — its commitment to the past experience of happiness which spurns the desire for its conscious re-creation. The psychoanalytic liberation of memory explodes the rationality of the repressed individual. As cognition gives way to re-cognition, the forbidden images and impulses of childhood begin to tell the truth that reason denies. Regression assumes a progressive function. The rediscovered past yields critical standards which are tabooed by the present. Moreover, the restoration of memory is accompanied by the restoration of the cognitive content of phantasy. Psychoanalytic theory removes these mental faculties from the noncommittal sphere of daydreaming and fiction and recaptures their strict truths. The weight of these discoveries must eventually shatter the framework in which they were made and confined. The liberation of the past does not end in its reconciliation with the present. Against the self-imposed restraint of the discoverer, the orientation on the past tends toward an orientation on the future. The recherché du temps perdue becomes the vehicle of future liberation.”

Horn uses this Proustian revisitation to great effect throughout the body of her work, but, in 1970’s Shoulder Extensions, (fig 5) something interesting has happened. In this piece and its documentation, Horn is not only transforming her own body’s history and its memory, but rewriting that of her art as well. These are three photographs of the same piece, published in three different catalogs: Rebecca Horn, published by the Guggenheim Museum in 1993; The Glance of Infinity, from the Kestner Society’s solo exhibition of her work, published by Scalo in 1997, and Body Landscapes from the Hayward Gallery in London in 2005.

In this piece, Horn transfers her eponymous symbolic horns to the shoulders, thereby extending the might of the wearer’s presence, suggesting prehistoric defenses, harkening too, to the infrastructure of wings, a recurring theme in her work, but now bare and flightless, honed into awls with which to poke holes in the sky.

In the close-up of the image in the Guggenheim’s catalog, there is something strange about the straps she describes as having been part of the piece. They are actually drawn, retouched, onto the surface of the photograph. This same image subsequently appears in the Glance of Infinity, this time with the note from Horn stating, “The two black sticks are tied onto both shoulders and across the chest, and connected by straps to the thighs. Each step the performer takes is transmitted from his legs up to both shoulder extensions, and is in turn reflected in obverse-scissor-like movements in the air.”

This is a beautiful image and a lovely idea, but it is a fabrication. This piece couldn’t actually have functioned as designed. (fig 8) The question is, did Horn make a further, undocumented iteration of this work, or did she simply decide that there was one? It is unlikely that an undocumented version exists, as she seems to have always paid a tremendous amount of attention to the evidentiary aspect of her practice. The unretouched photo appears in the London catalog, with the title “Bewegliche Schulterstäbe” which translates to “Moveable Shoulder Extensions,” but it is exactly the same photograph, without the painted-in straps.

If deliberate, in its disarming way, this curious exaggeration resembles nothing so much as a child’s lie, another unapologetic regression to a time when phantasy was as real as the mother’s breast, and just as necessary. Whether Horn accords this retroactive edit the full weight of a fully-executed piece of sculpture, or simply is satisfied with the revisions her perfectionist imagination has demanded, is a question only the artist can answer.

In an exploration of Horn’s visual lexicon, Toni Stoos, one of Horn’s chroniclers, compiles a dictionary of sorts, an indexical reference by which to guide the viewer through an early monograph. Recurring themes and objects are listed and delineated in what turns into a fairly loaded ring of mutually reinforcing tropes and motifs:

allergy, antenna, ash, bandage, bath, Buddha, butterfly, cage, circle, dance, death, dialogue, egg, elephant’s hide, eye, fan, feather, fever, glove, gold, hammer, headstand, illusion, insanity, kiss, machine, marionette, mask, mercury, murder, needle, oasis, paradise, peacock, powder, purple, razor, reptile, rhythm, scissors, skin, sphere, spiral, strait-jacket, strawberries, swing, tango, tears, touch, twin, unconsciousness, unicorn, wedding, widow, wing.

This lyrical list circumscribes Horn’s variegated and vigorous practice, and illuminates the far corners of her vocabulary. We see that Horn’s metonymic facility is enviable, and the poetry of it evokes a virtual shopping list of psychoanalytic concepts — death, illusion, insanity, the unconscious—all rich themes that the artist avails herself of again and again. Even more interesting are the symbolic referents of her materials employed in her uninterrupted amplification of the senses, which all point to an existence that is willfully and polymorphously perverse.

Many of Horn’s early sculptural and performative works find their origins in a series of sketches that Horn calls “The Hospital Drawings,” made during her confinement to the Sanatorium during 1968 to 69. They are quite literally the expressions of her physical yearnings, designs for unheard-of prosthetics that were destined to become her weapons for escape, the ever-present and torturous medical devices that populated her environment transmogrified into the instruments of her release. It is while wielding these that she would enter into the first round of her lifelong tournament against Thanatos.

As we sift through the images of her early work, a startling affinity with the underlying erotic aims of the Surrealists begins to emerge, stripping bare their raucous Dionysian sensibilities to their deeper foundations. In her own quiet, formal way, Horn has enlisted herself in the Thiasus, Dionysus’ ecstatic retinue of horned Satyrs (no coincidence there) and ravenous Maenids. She is to be a divine reveler, never again to be separated from the carnal, but henceforth devoted to the ritual pursuit of liberation, that very core of Dionysus’ mission. In the braiding together of mythologies, Horn mines the supernal in celebration of the mortal, deftly pilfering glowing coals from the pockets of the Gods with a Promethean sense of mischief.

In her attempt to reproduce a state of separation and isolation by virtue of her ‘garments’, she is re-creating the loss of sensation that was thrust upon her during her illness, but amending its import — she revisits the body’s history in order to transmute it, to bend the plasticity of memory to her will, hence transforming the past and defeating time. It is a form of magic, of conjuring, and through it, she initiates her participants into her own Thiasus, thereby substantiating her newfound powers of divine intervention. She is in the process of exempting herself from the laws of common man and beginning to tinker with the very elemental structures with which he defines himself. Marcuse, in describing the relationship of Eros to Thanatos, speaks of one of these structures eloquently:

“The flux of time is society’s most natural ally in maintaining law and order, conformity and the institutions that relegate freedom to a perpetual utopia; the flux of time helps men to forget what was and what can be: it makes them oblivious to the better past and the better future. This ability to forget — itself the result of a long and terrible education by experience — is an indispensible requirement of mental and physical hygiene without which civilized life would be unbearable; but it is also the mental faculty which sustains submissiveness and renunciation. To forget is to forgive what should not be forgiven if justice and freedom are to prevail. Such forgiveness reproduces the conditions which reproduce injustice and enslavement: to forget past suffering is to forgive the forces that caused it — without defeating these forces. The wounds that heal in time are also the wounds that contain the poison. Against this surrender to time, the restoration of remembrance to its rights, as a vehicle of liberation, is one of the noblest tasks of thought.”

And, I would argue, of Art.

Rebecca Horn does not want to forget anything. She remembers every moment of her trial, and is not about to let the responsible forces off the hook. Indeed, in the classic reversal that is so typical of those who have experienced oppression, she wants to appropriate the power of her oppressors, and wield it against them. However, with the Gods, she is up against some formidable adversaries. Conveniently though, they themselves are as fully subject to revision as their descendent fictions. And since Horn has amply demonstrated that she has no problem revising time and history, the Gods pose little in the way of threat now.

As in her 1974 piece Keeping Hold of Those Unfaithful Legs (fig 11), Horn conjures her own fantastic beings in a type of bestial genesis — indeed, several of her earlier body extension garments evoke the freakish and monstrous, although with as much evident affection as Mary Shelley bestowed upon Viktor Frankenstein’s Creature.

Arm Extensions (fig 12) from 1968, the artist extends the wearer’s encased arms into the ground, the thick stumps reminiscent of a gorilla’s, almost primeval in its heavy rootedness and overemphasized connection to the earth. The color red refers inescapably to blood, and when viewed through that lens, suddenly transforms the wearer into a rigid supporting structure, a bridge for what feels like an errant and herniated aorta jutting from the body of the earth. Oddly redolent of a classic child’s toy, it invites a giant godly thumb to come up beneath it and press to relieve the tension, collapsing the entire assemblage.

In Overflowing Blood Machine, 1970, (fig 13) she turns the body inside out in a literal inversion of the circulatory system, removing its visceral and epidermal protection, changing this most vital and delicate of the body’s fundamental mechanisms into a cage of sorts, rising, bridging the shoulders and plummeting back into a murky red pool of essence. The rawness of the image is startling, suggestive of vivisection and every interior fiber laid bare, ceaselessly open to overwhelming sensation. With works such as these, Horn seems to be asking, “What is corporeality? How does the body encapsulate and imprison us? Alternately, how may it liberate us?”

In Séance for Two Breasts, (figure 14) also from 1970, we have yet another bridge, spanning the mouth and each breast separately. The title suggests an attempted communication with something that has died. It’s as if, by isolating one from the other, Horn is speaking to her re-awakening sexual self, her gendered self, through twin “Cones of Silence,” rendering her intracorporeal conversation even more private for the effort.

The inescapable flavor of horror does permeate Horn’s work, a wry flirtation with the abject that manifests itself in her tangential references to the violence to which the human body is so very vulnerable—and in no sense are we more vulnerable than in our yearning. Ironically, in the annals of the Gods, it is their yearning that grants us entry to the Pantheon. Yearning is the great weakness they share with us mortals. In our mythologies, for all their power, the Gods too are constrained, and their epic and obsessive struggles with their own pathetic limitations inform all mythological, legendary and religious traditions, east and west.

But what Horn plays with here is the horror of craving, the threat of the object’s disgust in the face of our desire, the loss of that object, the infant’s incipient trauma at the hands of the kleptomaniacal Fates. Some of her pieces tend to a quiet sort of melodrama, but Horn is a dramatist, after all, her creations functioning as a silencer-like extension of the mythological canon, her aim disciplined and marksman-like in its caustic precision. In considering this, I would not be the least bit surprised to find Douglas Sirk listed among her many influences.

In her early work, Horn is teaching herself execution, eschewing the compulsive agitation of the surrealists from whom she evidently also draws some inspiration in favor of an elegant formalism. Control itself is a ball in her game of psychological catch. At no point does Horn topple wholesale into a sea of utterly appeased sexuality, rather, through mechanical means, with meticulously constructed devices that are meant to literally harness that libido and direct its power, she learns to formulate an exquisitely crafted acknowledgment of its primacy. This is Marcusian enlightenment at its zenith: the apotheosis of sublimation.

These works are personal, intimate, her commentary and dialectic geared to the dismantling of our individual mechanisms of alienation, and not meant to function as a critique of the larger social fabric. Horn addresses each of us, one at a time, and proffers no ontological conjecture, directing our attentions instead to our own sensual reactions, neatly sluicing our physiological responses to her work by reminding our minds of the polymorphous presence and primacy of our own bodies.

In her effort to heal the separations between our conscripted bodies and our alienated psyches, she employs a plurality of resistances, ensuring that no single strategy congeal into an unstable core of insurgency. Horn’s early creations alternate between playful gender appropriations — team-enabled embodiments of exaggerated penetrative aspirations — and the more yin-tinged embodiments of vessels in which to cross the oceanic with a carefully chosen few. She has been adamant about the absorption of the spectator into the realm of the participant, deliberately constructing arenas in which to stage the bouts of conceptually procreative mutual violation the French phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty speaks of. In doing so, she seeks to harvest the enlightening product of that union. Horn writes, “Personal Art: For each performance in the years 1968-1972 the number of participants was limited, because intense interpersonal perception is only possible in a small circle of people. Each situation should result in dissolving barriers between spectators and active performers. There should only be participants.” An attitude which also calls to mind Alan Kaprow’s essay on the ‘Elimination of the Audience’ from 1966.

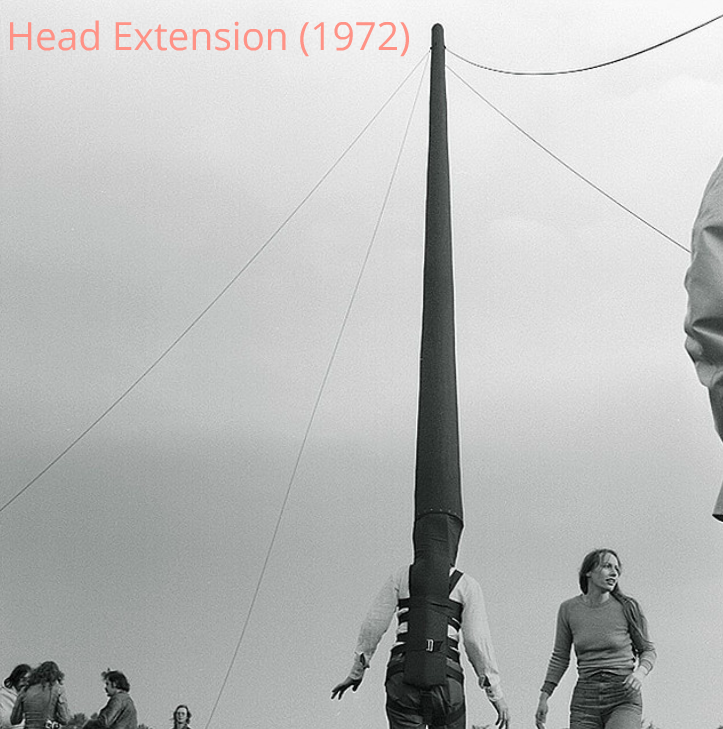

Head Extension, (fig 15) from 1972, a further, more aggressive iteration of her ‘joust’ is a perfect example of this practice: